Fish Tugs of the Greatest Lake

The Drum Lesson

By Steve Ceskowski

1980 was a banner year for southern Lake Michigan chub fishermen.

In spite of DNR forecasts to the contrary, large lifts of chubs of many year classes were being consistently produced, and the alewives were finally beginning to cease to be much of a problem. What was a problem, was the weather. A series of windless sub-zero weeks hit in early February. Southern Lake Michigan froze hard and deep. Winter fishing was a challenge overcome by the advancing technology available during the last half of the 20th century. Strong diesel engines and sturdy, close-framed steel hulls could overcome the ice ringing our shores allowing tugs to break a way to open water offshore. But 1980 was something else!

Phillip Anderson's fish tug Ida S. was fishing out of Chicago using the Illinois license of Union Fisheries. Herman "Sport" Johnson captained the 55' Burger fish tug with a crew consisting of Charles "Buzz" McDonald, Lorman Greenfeldt, and the author, Steve Ceskowski.

We had been fishing three ten-box gangs of 2 5/8 " & 2 3/4" mesh nets producing four-night lifts in excess of a ton each....until February. The lake froze so hard we were unable to break our way even a few miles off Chicago, not to mention the two and a half hour run to the "flats" where our nets were. Huge ore carriers and bulk carriers were frozen-in solid offshore unable to move for weeks. The Coast Guard was active trying to keep the Soo locks cleared with their heaviest ships and dispatched a buoy-tender named Arundel down our way to try to free the trapped lakers. After three weeks of inactivity, the weather broke and temperatures rose enough for us to try to make a lift. By then our nets were three weeks out.

We slipped our moorings on the Chicago River and made our way out the locks into the lake. We knew if we were successful in reaching open water that we would have a very long day or two ahead of us. We packed extra food, coal for the stove, and gas for the pump engine. A northwest wind had pushed the pack ice offshore about six miles and we made good time through open water. We soon found ourselves amidst pancake ice and then the "growlers" the preceed the pack ice. The Ida S. was built with fine lines that soon challenged the ever thicker pack ice. The Cummings diesel pushed us ever deeper towards the prospect of open water somewhere offshore. The noise of breaking two feet of solid ice can be deafening for those inside an all-steel tug.

As we made further progress offshore our speed began to diminish as the ice became ever thicker. We began to see the trapped lakers outside of us, a virtual "city" of mariners trapped in the solid form of the substance that gave them the name "sailors". But they were not sailing, and a short time later, neither were we. Trapped! We tried backing and charging, but it was to no avail...we were stuck! I popped the pilot-house hatch and stood on the house with my binoculars scanning the polar-like scene all around us.

I imagined that things like penguins and seals might come into view any second!

What came into view was the Coast Guard ship Arundel. She had sailed outbound in our track to try to assist in breaking out the lakes visible on the horizon. The Arundel hailed us on the radio as they neared us and asked if we needed help returning to Chicago. After a discussion among the crew of the Ida S., we decided to ask the Coast Guard for a tow outside to open water. The Coast Guard obliged and came alongside us. We threw them a thin line which they attached to a towing hawser. We hauled the hawser aboard and secured it to our bow post. Under full power, off we both went. We reached open water about a half hour later. The Coast Guard advised us that their radar showed open water all the way to Waukegan. We slipped the tow hawser and thanked the Arundel and off we went in search of our buoy.

|

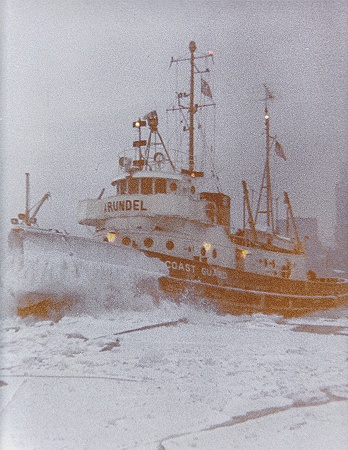

| Emerging from the morning gloom, the USCG Arundel breaks ice beneath the Chicago skyline. Photo taken by author Steve Ceskowski from the pilothouse hatch of the IDA S. on the day of the incident. |

We found the first gang of nets and lifted and cleared them in about four hours for about 3000 pounds of chubs. The fish were in excellent condition for being three week out. We had a discussion about what to do next about our next gang and the full gale warnings being announced on the radio. The weather was still decent that afternoon so we decided to find the second gang and lift as many boxes off it as we could before the weather turned dirty. We handily found the second gang and began to lift. This gang was really loaded and the weather was really turning ugly as the wind and swell began to come alive. We cleared half the gang for about another ton of chubs. The wind was shrieking and the waves were getting huge. The forecast was for a full gale that night with plummeting sub-zero temperatures for the next three day. We decided we were not returning to Chicago to be trapped in the ice again; that we would head northwest into the teeth of the gale and dock in Waukegan. It was now pitch dark and snowing, with winds blowing over 40 knots.

"Sport" Herman asked if we should put the buoy on and head for shore or if we should bunch the last five boxes, fish and all, into the tug. Facing the prospect of further delays due to sub-zero weather, we decided to bunch. And bunch we did. We had nets all over the forward half of the Ida. With fifteen boxes tied securely aft and 5000 lbs of chubs in totes, it was beginning to be very difficult to move around. With five more boxes of nets forward with perhaps another ton of fish in them, the Ida S., stout as she was, was beginning to show the strain....as were we.

We pulled the lifter and pan in, secured all our doors, wedged whatever was loose as tight as we could and set course for Waukegan. The wind began to just shriek, as ghostly a howl as I ever heard on the lake. The building swells were attacking our beam as we quartered our way for port. The Ida was handling the situation as well as she could. The temperature was dropping like an anvil and we were quickly making thick ice on the house. The tug was rolling ever more sluggishly and the Wood-Freeman auto-pilot could not hold her course, so we took turns hand wheeling the tug, bracing ourselves against the combers as they raked our starboard side with a seething sound. The crew kept the pump going and gassed as water penetrated the chinks in our doors. We were making progress as we skirted the edge of the pack ice that our radar showed ended at the Waukegan light a dozen miles ahead.

The waves were becoming just immense. The radio said they were twenty to twenty-four feet that night in the full gale, marching straight down out of the north-northwest, the full fetch of the lake. The Ida S. shivered and trembled from stem to stern as wave after wave attacked us. Herman Johnson had to check the engine down as the ride was becoming violent. We scrambled trying to secure and retighten our deck load without crushing our legs. Herman then began to jockey the throttle up and down to the rhythm of the waves, checking down as green water cave over the house closing the exhaust baffle. But little by little we were falling into the lee of shore as the waves began to shorten. The ice ended right at the welcome green glow of the Waukegan lighthouse, but not before we had to surf over the Waukegan Reef, just a mile offshore. Bathed in the city lights of the harbor, the breakers on the reef looked like something from a scene from the North Shore of Hawaii...just monster waves, and we drove right through the midst of them. Whew!

It was a relief coming down the piers as I began to find lines to tie us to the City Dock. We had some 1 1/2 poly lines that I readied. We opened the door as "Sport" drove us up to the dock. I was amazed at the amount of surge in the harbor from the gale outside. The tug was bucking 5-6' feet up and down with every surge. We secured lines and took a well deserved breather, stoking the fire against the blizzard outside at about 8 pm.

The lines did not last long. They were old, chafed, and brittle; parting again and again. Our lines were fine for tying the tug in the Chicago River, where it was said a shoelace would hold secure...but not on a night like tonight. The ride at the City Dock had exhausted all our lines...there was nothing left to splice. We untied and idled in the harbor while we called the Ida S.'s owner, Phillip Anderson in Kenosha, on the marine radiotelephone advising him of our situation and asking him to deliver us new lines so we could secure the tug.

Phil said the roads were bad and that he had a "drum lesson" that night and that he probably could not help us! I could not believe what I was hearing! I told Herman to drop me off at the U.S. Gypsum dock, so that I would find us lines. Timing the surge, I leaped off the tug into a snow bank about waist high. I walked up to Bert Atkinson's inactive fish tug, the Clifford J., boarded her, and removed three long coils of 2" nylon hawsers he had stored in reserve. I signaled Herman and he bought the Ida S. alongside the Clifford J. and I handed the lines to Buzz and Lorman, then I climbed aboard, my damp clothes frozen stiff as cardboard.

We decided against trying the City Dock again and chose to lay against one of Falcon Marine's barges, that was tied to another barge, that was tied to the seawall. There the surge motion was dampened and we finally rode gently into the night. We then began to dress our load of chubs until 1:00 am when Phil Anderson finally arrived to take Buzz and Lorman back to Kenosha. Phil called my wife and she arrived to pick me up and drop Herman at his apartment in Waukegan.

The next day we returned to the tug about 10am braving the huge drifts of blowing snow. We cleared the last five boxes of nets and dressed long into the afternoon. In all, we weighed-off 7200 lbs of chubs and probably threw another 400-500 lbs of chubs that froze onboard overnight away. It was the most fish I ever saw on a tug at one time.

Postscript: We finally retrieved our third gang a week later, one month out.

We salvaged about 1200 lbs of chubs, and set two gangs back. The weather had finally mellowed and we resumed fishing out of Waukegan. We returned Bert Atkinson's lines back to the Clifford J., and were supplied with newer lines from Kenosha. As to Phil Anderson and his "drum lesson", let's just say that Sport, Buzz, Lorman, and myself, never wanted to hear those words spoken on a fish tug ever again!

|