Fish Tugs of the Greatest Lake

Twenty Hours To Nowhere

by Lyle McDonald

From the Grand Marais Pilot, April 23, 1975

Original Editor's Note (1975) : Lyle McDonald lives in Laurium now as a successful retired mining equipment sales engineer. His life has been far removed from the rather quiet pace he now enjoys however, for Lyle is the fishing son of Alex McDonald, and nephew of Jim, Gordon, and Charlie McDonald -all names synonymous with Lake Superior commercial fishing from 1910 to 1954.

In 1930 Alex and Lyla McDonald came to Grand Marais from "Soo" Canada and raised their family of six sons and two daughters literally in Lake Superior's surf.

Son Lyle, as did all of the boys, put in his time on the big lake. He lost his own tug, the "Vernon S." in a fog shrouded collision with a freighter. (Burt Township Trustee Walter Krackowski, was a seaman on the Vernon during that sinking).

Lyle battled the big one after Uncle Jim and Tony Tornovish went down in the ill-fated year of 1945 which also saw Lake Superior claim the lives of Frank and James Vaudreuil, Scott Chilson and Frank Green.

We lived in Grand Marais during the incident Lyle writes of below. Recalling how we stood at the school library window with his younger brothers Kenny and Bill (PeeWee) during the long morning vigil, we asked Lyle if he would write us some notes about this incident and others. The "notes" we asked for are reproduced below exactly as we received them.

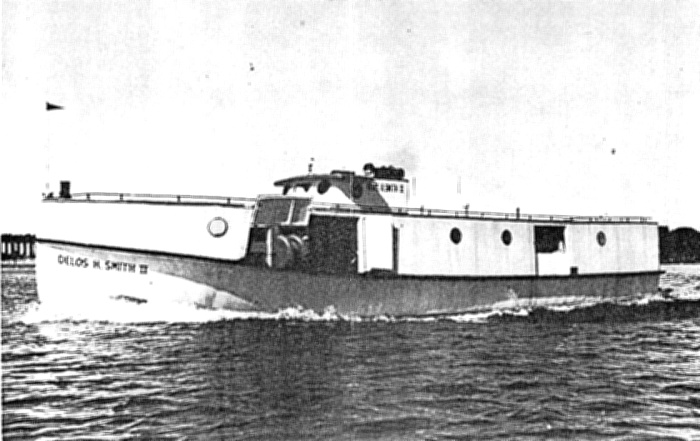

The Delos H. Smith II

Each of us who have sailed the lakes and seas are sure that the bad storm we were in was the most severe-including myself. I want to relate to the storm that caught us out of Grand Marais, Michigan on December 5, 1950, on the fishing tug Delos H. Smith II. Those who were in Grand Marais on that day, I'm sure, will remember and agree with me that it was the most wicked storm that a fishing boat ever returned from.

The tug Delos was a magnificent fishing ship. She was 55 feet long, constructed of steel, with an aluminum house. The sturdiness of the steel, the light weight of the aluminum, the flare of her bow, and the reliability of the engine and pumps were among the material features that permitted us to keep her afloat throughout the severest of gales.

The crew of Dennis Manilla, Charley LeFebvre, John Morrisey and myself, left Grand Marais harbor that morning in calm and overcast winter weather. We ran almost two hours to our nets that were set on the bank outside Big Two-Hearted River, lifted the nets and started to set them back. The nets had approximately 500 pounds of trout, and the day had been quite routine.

When we had three boxes of nets left to set (approximately 20 minutes), we began to see and feel the 'dead roll' that usually precedes a strong wind-and the sky turned purple in the North. I went aft and told the crew to put the clutch in, set the nets as rapidly as possible, and we headed for Grand Marais.

The remaining nets were set in about 10 minutes, and we sailed full throttle for port. The crew, as customary went forward to start cleaning the fish. At that time the lake turned all white, and the wind hit with unleashed fury. The men did not get started dressing the fish, because it was imperative that the boat be made shipshape, with everthing movable lashed down and braced. Strong-backs were installed in all gangways, and the engine and pumps lubricated and checked.

The rapidity in which the size of the seas built, and the fierceness of the wind are impossible to comprehend. We were approximately an hour and a half from home, and it became obvious that attempting to enter Grand Marais harbor would be sheer suicide. As all sailors would have done, we turned completely around and headed for Whitefish Point, 40 miles to the east of us.

Now we realized another bad factor of this freak holocaust. It was not blowing from the Northwest, as most bad blows, but was coming directly out of the North. This caused us to be exactly in the trough of the seas on our course to Whitefish. Had the wind been from the Northwest, it would have been over our aft port quarter, and we may have been able to ride it to Whitefish Point.

The tug Delos had pilot-house controls, so that steering, speed and clutch were easily accesible to the captain. Running in the trough, it was advantageous in many ways to vary the speed, thus making it easier on the ship, and still cover distance.

Despite the fact that the waves were breaking over the side, we seemed to be weathering quite well, when suddenly a giant wave came from nowhere, caught us flush, and stove in the forward gangway on the port side. The feeling caused by the gaping hole with the twisted aluminum and angle iron reinforcement was the closest to complete panic that I have ever experienced. It also revealed the one poor design feature on an otherwise near perfect ship. Instead of sliding doors, these were folding outward type, secured to the ship with hinges and stove bolts. Because the hinges and bolts held, the twisted metal made it impossible to plug the hole with planks and mattresses. The doors had to come off first-and fast, as we every wave was pouring barrels of water into the ship.

Charley LeFebvre was assigned to steer south (before the wind) as slowly as possible, yet maintain steerageway. This was the only diection in which it would be possible for us to work on the broken gangway, however that course headed us for the shore, and beaching meant almost certain drowning for the crew, and the destruction of the ship. To remove the gangway, it was necessary for me to reach outside and hold the nuts with a crescent wrench, while Denny Manilla used a screwdriver on the inside-and those damned stove bolts were rusted. Even going before the wind, the combers were breaking blue water over the full length of the 55 foot ship. With every wave, I had to duck my head in to save it, yet maintain hold of the only wrench that fit. After a few minutes that seemed an eternity, the doors were off, and John Morrisey had gathered planks and mattresses from the decks and bunks, so that we were able to do a remarkably good job of plugging the hole, under the circumstances.

Charley had done a yeoman job of holding her before the wind while we were repairing the damage, however I was fearful that we may be too close to the beach to turn around, and also whether the ship could stand the trough of the sea long enough to to get her headed up into the wind, which was now the only possible direction in which we had any possible hope of survival. The visibility was almost nil, and early winter darkness approaching. We put her hard to starboard, goosed the throttle, and prayed that she would come about. She did.

The possibility of survival now depended upon the ships ability to be bouyant enough to rise out of one sea before the next one hit her, the reliability of the engine, the sturdiness of the rudder cables, and most of all, the human ability to maneuver the ship so that all big waves hit her on the starboard bow. A big wave on the damaged port bow would knock out the repair job, and probably fill the boat with water. To accomplish this it is necessary and essential to work with the 'rhythm of the seas'. In a bad storm, the size and actions of the waves are not consistant. Some waves will crest and break at 10 feet, others will at possibly 30 feet, consequently the distances between waves also varies. What we had to do may be likened to a person walking up a hill and taking two steps forward and sliding back one. In this instance it meant keeping the rudder at starboard until the ship was almost directly into the wind, then let her fall off a little, never going beyond enough to expose the damaged port side.

As captain of the ship, it was my duty and responsibility to make the decisions and handle the boat, but I surely could not have done anything were it not for the excellent, experienced gutsy crew. I take little credit for the decisions made during this crisis, because when mens lives are endangered, he does what has to be done, and can be done.. In this instance, I thank God for a good crew of seamen, a worthy ship, and the power of us that no one panicked.

Of course, the busted gangway created the greatest turmoil and danger of nonsurvival, and after we got headed into the wind, our tensions eased somewhat, however we were still a long night away from the thought of seeing our loved ones again. In heading into the wind, going nowhere, just maintaining enough speed to for steerageway, the ship does not take such a beating. However, because we were favoring the port side, the seas were hitting us on the starboard bow in such a manner as to cause a twisting action on the ship. This action could cause rivets to shear in the hull. Along with the fear of the engine stopping or the pumps failing, there was little to lesen the tension.

After heading into the wind in this manner for approximately two hours, there was no sign of the wind abating, and although the ship was weathering well, my arms were very tired, and the yellow streak along my back became very irritable. It was then decided that we would split the four man crew into two teams, with Denny steering and Charley as watchman for an hour and myself steering and John watching for an hour, alternately.

Because the night was now pitch black, it was very difficult for Denny to pick up the rhythm of the sea. The compass is not entirely reliable in a situation like this because it often reacts too slowly, when the ship is pummelled so fiercely. We wheeled together for a short period, until he felt that he could handle her, and we all felt relieved. Denny had worked many years on the Delos, and this night handled her to perfection. We all knew that a ten second loss of control could spell curtains for us all.

By 10 p.m. the wind still showed no sign of abating, however we had weathered over seven hours, and began to get the feeling that we could probably ride it out as long as our fuel lasted, which we estimated to be about 20 more hours.

Shortly after midnight, while John and I were on watch, there appeared a bright streak on the horizon from Northwest to Northeast. When we were on the crest of a sea, it was visible, initially like a chalk line and became wider. It looked very eerie, and I asked John what he thought it meant. He replied, "Maybe it is going to blow harder." That response was like being hit while down. What was happening was that the sky had broken, and within a short while, the stars were shining in the heavens, and shortly after that the wind seemed to begin to recede. The Grand Marais harbor lights became visible, and never looked more beautiful.

Shortly after the late December daylight, the wind subsided enough that we dared to turn around and head before the seas. After almost 20 hours, we were within a few miles of where we were when the storm hit.

The trip to the harbor and through the piers was uneventful, however the large crowd of loved ones and townspeople who greeted us at the dock was very gratifying and heart-warming. We learned later that my mother, Mrs. Lyla McDonald, was first to spot us. Shortly after sunrise, she saw a flash of sun reflecting on a window, long before the boat was in sight. As we had no radio or other means of communication, only the Lord above knew where we were since early the morning before. Albert Grasser, manager of Smith Bros. Fisheries had made hourly visits to all the families during the night to report that the boat had not been heard of at any port, and was in the process of organizing search parties.

A fond memory of the adventure occurred practically before the ship was completely moored, when the respected and beloved Captain Jim Thorrington stepped aboard and said: "Nice piece of seamanship, men."

|

|