Fish Tugs of the Greatest Lake

Herring Are Silli

By Clay Perry

The World War II years were a boom time for the Great Lakes fishery: the need to feed a hungry army placed great demands on commercial fishermen. This 1945 article from Collier's magazine draws a vivid portrait of that era.

*******

"SILLI" means herring to Michigan's colorful Finns, but don't let it mislead you. Fishing in Lake Superior is a man-sized job. Here are the men who are keeping the Army in fillets.

When America thinks of commercial food fishing it thinks of its seacoasts. Yet fresh-water commercial fishing in the United States, under the impetus of war, has become big business. It has grown up swiftly from haphazard operations out of Great Lakes ports to a co-ordinated industry that furnishes thousands of tons of fine food for both armed forces and civilians.

Most important of the inland fishing states is Michigan, with 1,600 miles of shoreline (more than any seaboard state) on three vast Great Lakes. An investment of $3,000,000 in more than 1,100 boats and gear keeps 3,000 fishermen at work gathering an annual harvest of herring, lake trout and whitefish. That averages 30,000,000 pounds of fish a year and nets the hard-working fishermen more than $4,000,000.

Prize food fish of the Great Lakes is the Lake Superior herring, the firm succulent variety that commands a premium price anywhere in the world. Even in normal times, Lake Superior herring, along with whitefish and the huge lake trout command a wide market, even in the seacoast states.

Ideal fishing grounds for herring are in the lee of northern Michigan's Keweenaw peninsula, which juts its rugged 45-mile length straight out into the cold blue waters of Lake Superior, the world's biggest - and roughest - lake. This peninsula shelters a large bay from the fierce nor'westers - although not from the equally severe nor'easters. Here within sight of a land of lakes, forests and mountains that is a vacation paradise in summer and a fishermen's hell in winter, is one of the most important sources of food fish for the Army.

While lake trout and whitefish are year-round staples for Upper Peninsula fishermen, herring provide the most hectic and hazardous action. The mid-winter season is short and severe -three or four hard-bitten weeks of lashing gales, blizzards, bitter cold and sometimes sudden death and disaster, as hardy fishermen gather millions of herring from the large schools that gather to spawn on the reefs and shoals off Keweenaw's southeastern shores.

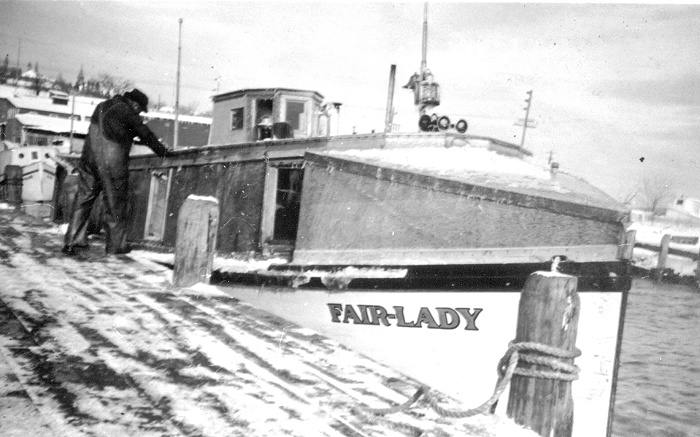

The Fair-Lady at Bayfield during herring season.

Keweenaw fishermen are a tough and colorful lot. They are mostly second and third generation Finns who have managed to retain their nationalistic identity, customs and language since their ancestors came to this land years ago, to fish, farm and work in the forests and the deep copper mines.

They need to be hardy and brave.

The 1943 herring season got off to a heartbreaking start with the worst storm in thirty years, just as the run was beginning. A three-day howler, sweeping across 200 miles of icy lake, washed so much sand into harbors and ports that huge dredges had to be hired in a hurry to clear the way for the boats, while docks and other equipment were badly damaged and some ports were made useless.

Bigger and Better Herring in Season's First Catch.

The 1944 season on herring opened a week late due to the warmer weather. However, the fishermen were pleased when their first netting showed that the herring (catches) were running larger in size. The Michigan Conservation Department's figures for the total catch of herring in all three lakes - Huron, Michigan, and Superior - are 7,249,190 pounds.

But the price went even below the 1943 ceiling of three cents per pound, despite the fact that OPA regulations were lifted, and no ceiling price was imposed for "herring in the round." The reason for this is believed to be the fact that the big city packers, a month before the 1944 run started, had a carry-over of 2,500,000 pounds of herring. Nevertheless packing went on full blast, with the Army taking about the same amount as the year before, and three filleting plants operating to provide frozen fillets.

A midwinter trip to the Big Lake with Captain Henry Tormala, out of Portage Entry, is an unforgettable experience. His boat, the Superior, is a 35-footer, with broad beam, enclosed against the weather from stem to stern, metal-sheathed to combat ice. It is owned by Captain Henry and his brother, Aldrick, manned by a Finnish crew of five.

The Superior leaves port before dawn in the teeth of a knifing gale, with snow driven before it. The boat carries several gangs of 40 nets, each 250 feet long, 35 to 40 inches wide, fitted with buoys and anchors. Thrust out from a hatch near the bow is the bristle-toothed "lifter" -motor powered - that drags up the loaded nets. A barrel of water has been heated, it will be thrown on the lifter to keep it from freezing. Amidships is a roaring fire in a tiny stove, on which always simmers a pot of kaffi, the superb Finnish coffee.

Captain Tormala heads into the hammering, pounding waves and screaming wind which toss the boat badly, holding his course for his chosen reef. Inside, the crew hug the stove and hang on. An hour or more of this, and a rear hatch is opened -and the icy blast roars in.

Out goes the buoy, as tall as a man, anchor, and then the nets, unfolding from their trough shaped net boxes. Down they go, ten fathoms, the legal limit of depth. Nets are of Sea Island cotton and cost $500 to $600 per gang for material alone. The fishermen weave them and they handle them with great care.

"Paava!" growls a veteran crewman, which is a Finnish "hello" to the cold and tumultuous wind. "We get plenty silli (herring) maybe. Plenty raha (money) -maybe."

It takes several hours to set the four long miles of gangs -some big boats set twice as many -and we head back to port for a big meal of fresh herring -or as a special treat, lake trout baked in a pit on hot stones, or whitefish, fresh or smoked.

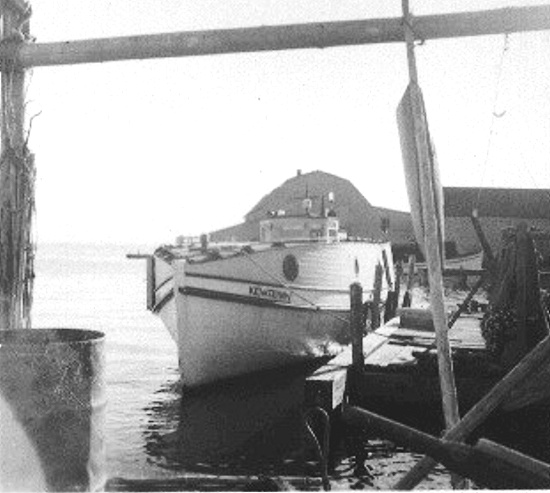

The Keweenaw, owned and operated by the Finnish-American captain F. Arnold Rautiola, shown at Portage Entry, scene of this article.

Next morning, we head out for our reef again. There is a heavy swell from the previous blow, and the wind is rising with the sun. Sharp snow pellets hammer at the hatches and glass windows as we plow out to see how many tons will be lifted that day.

Over the nets, a hatch is opened, and the first net is hooked to the curved teeth on the lifter cylinder. The motor is started, and the net begins to rise with its load of herring caught by the gills -a flopping, squirming, shimmering bouquet of fish. They roll in over the cylinder, and the crewmwn grab them hand over hand and "choke" them free, tossing them into wooden boxes. They work at mad speed, barehanded in the icy gale.

These Finns, among the best fishermen in the world, will handle 20,000 to 30,000 fish, one by one, in a day's haula (haul).

On this particular day our 5-man crew took four tons of herring. One day last winter, 32 tons were delivered at the Great Lakes Fisheries packing plant. We also karistaa - that is, set the nets for tomorrow - and paying out these miles of web from a pitching boat in a blizzard, near dark, is something to give a Gloucesterman pause.

At the home dock, trucks are waiting, and the catch is hurried off to the packing plant at Houghton or Hancock or one of the smaller ports, to be cleaned, boned, filleted, day or night, and then quick-frozen for shipment to the Army Quartermaster Department. A by-product of packing is delicious herring roe -as good as Russian caviar.

Michigan's big lake trout are taken in nets, by trolling and by bobing through holes in the ice. The ice angler is a human polar bear, scorning the huts and stoves used elsewhere. His only shelter -if any - is a tiny triangle of canvas set up to the wind.

Many an ice angler -sometimes whole squads of them - is carried out on drifting floes. Some drown, and thrilling rescues are common, the fishing boats crashing through the ice to get to the marooned men, with the Coast Guard racing to help.

Lake trout caught through the ice run up to 25 to 30 pounds, but the biggest are taken by deep trolling in summer. Many 50-pounders have been taken by sports fishermen, and a commercial fisherman once brought in a 56-pounder.

Deep lake trolling for trout has become a national sport, and Keweenaw held the first National Trout Derby in 1941, with 1,200 entries, a colorful two-week fiesta that will be resumed after the war.

Lake Superior leads all the lakes in big trout. It yielded the first seven of ten prize winners in the Field & Stream contest for 1941 and 1942. The biggest lake trout entered in the 1944 contest, 53 pounds, came from Lake Superior, and an even larger one, 54 1/2 pounds, was caught but not entered. Commercial catches of trout in Keweenaw waters have jumped from 45,323 pounds in 1940 to over half a million pounds annually in the past four years.

"All very fine," says the Finnish fisherman. "I'll take herring."

|